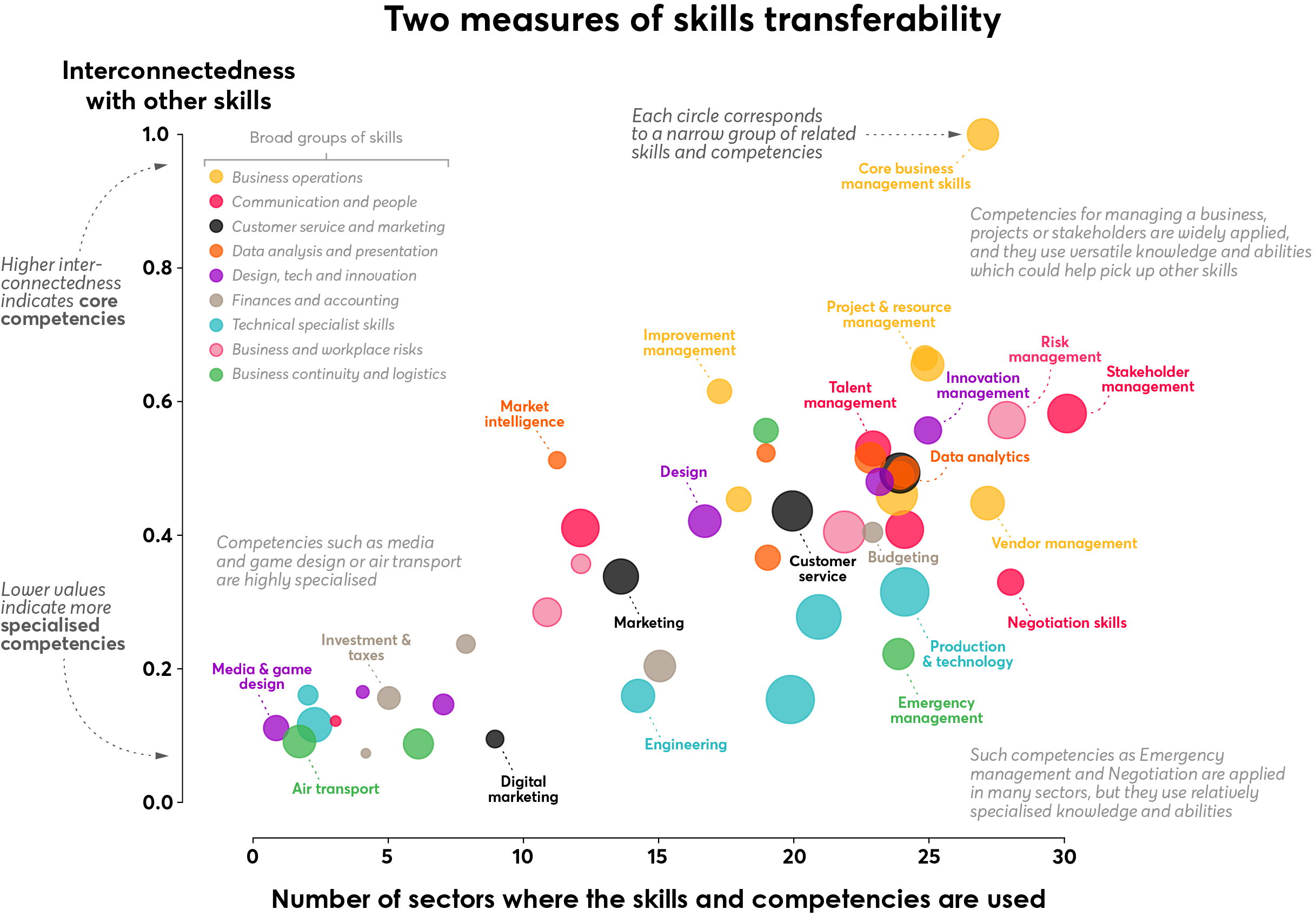

Notes: Each circle corresponds to a group of related skills and competencies, with the size indicating the number of skills in the group; colour indicates the broader skills type. The hierarchy of skill categories was identified by using graph community detection (similar analysis can also be applied to more granular skills categories). The interconnectedness of skills groups was assessed by using the eigenvector centrality measure from network analysis; it is normalised with respect to the group with the highest centrality score (i.e. core business management skills).

Firstly, we ascertained the number of sectors in which a particular group of skills is used. Possessing skills that are widely-applied will help workers to transition between different sectors. Among such skills, we found examples that are perhaps less commonly listed as transferable, including vendor management, risk management and innovation management.

Secondly, it is possible to assess skills’ interconnectedness with other skills, based on the similarity of their underlying knowledge and abilities (owing to the detailed nature of the SkillsFuture skills frameworks). This allowed us to distinguish between core competencies, such as business management and stakeholder management, and other skills that, while still being widely applied, use more specialised knowledge and abilities such as negotiation, emergency management and engineering.

Identifying highly interconnected skills may help workers to identify their core competencies and may help learners to choose between different types of retraining and upskilling. For example, stakeholder management skills are connected to other communication competencies such as talent management and learning and development, as well as skills related to business operations, such as change management and core business management.

What else can you do with a skills framework?

The section above illustrates just a handful of applications for a skills framework. By enriching the framework with real-time data on job vacancies, it would be possible to track changes in regional skills demand, evaluate the market value of different skills and competencies, and identify the emergence of new skills.

By incorporating the latest insights on advances in task automation, we can support workers at risk of being displaced by automation, to make transitions towards more secure employment. Similarly, to tackle the economic downturn, workers displaced by COVID-19 could be supported by tailored reskilling and career guidance.

Importantly, if the same skills framework were to be used by training providers and universities, it would enable a greatly-improved mapping of regional skills supply and identification of skills mismatches.

We are building the UK’s first data-informed skills framework

Detailed occupational and skills frameworks can ultimately provide a more holistic view of pathways between different jobs. Having a “map” of the landscape of jobs and skills will be essential for efficiently responding to labour market disruptions, especially at a time when the UK faces an economic downturn and needs to “level up” and redeploy its workforce.

The challenge is that skills frameworks should be as inclusive and timely as possible, but developing and updating expert-designed frameworks is an extremely slow and labour-intensive process. To explore an automated approach, Nesta released the first open, data-driven UK skills taxonomy in 2018 by using millions of online job adverts. However, we recognise that not all jobs are advertised online and not all necessary skills are mentioned within job adverts. To avoid these pitfalls, in the next version of the skills taxonomy, we are combining the timeliness and localisation of job adverts with the breadth of an already existing expert framework (ESCO), to ultimately arrive at a more inclusive and fully open-source skills framework.

Our manifesto on the future of work called on the Government to adopt a live skills taxonomy, which would identify the skills needed for different jobs. As we now repeat this call, the use cases shown here, as well as our project on mapping career causeways, demonstrate the potential value in building such a taxonomy and helping workers to navigate an increasingly uncertain labour market.

For more details about the particular skills frameworks, please contact SkillsFuture Singapore.

The methodologies for comparing occupational skills sets, finding data-driven hierarchies of related skills or jobs, and identifying core competencies have been developed further and described in the recently published report on Mapping Career Causeways: Supporting Workers at Risk.